Before the age of radio, television, cameras, and social media, paintings served as the primary means to deliver images and ideas to a mass audience. Artists used paintings to transmit ideas about American leaders, raise awareness about important events, comment on and critique the American Revolution, and pass the ideals established after the war onto future generations. However, those lofty goals didn’t ensure accuracy. “They document the idealism, they document the aspirations, but they are not necessarily documenting exactly the way it happened,” says Paul Staiti, a professor of fine arts at Mount Holyoke College. Despite the inaccuracies, Staiti believes these images continue to tell important stories about crucial points in American history. With the help of art historians and history professors, Re-enact curated seven images that portray some of the most important people and moments of the Revolutionary War.

1. Fashion Plate

Thayendanegea, a Mohawk leader and colonel in the British army, was known by his English name of Joseph Brant. Artist George Romney painted Brant during the Mohawk chief’s trip to England to discuss the Iroquois Confederacy’s role in the war. Brant was instrumental in convincing the Iroquois to join the British side and proved to be a persistent problem for the colonists throughout the war. Michael Galbon, the curator of the Seneca Art & Culture Center, says because England lacked proper Native American clothing, Brant improvised his attire and took inspiration from English fashion. Brant’s clothing style differed from traditional European dress to such a degree, however, that it became viewed as distinctly Native American, despite its improvisational origins. “Even at the time, when that style of dress was mentioned, they literally called it Indian dress,” Galbon says. Only the headdress, however, made of porcupine quills and mallard skin, is Native in origin.

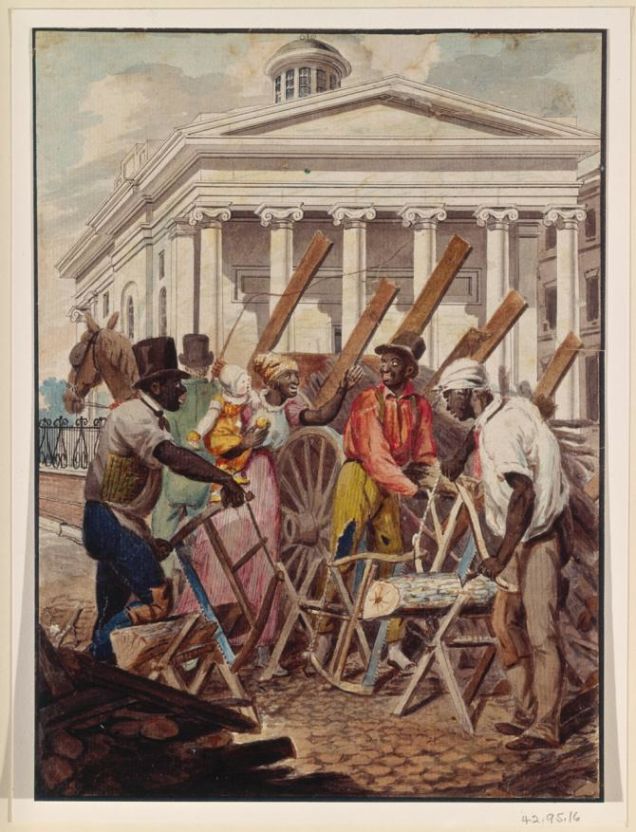

2. Outsider Art

John Lewis Krimmel was born in Germany to a family that made sweets. He came to America in 1809 to stay with his brother in Philadelphia. An avid sketcher and immigrant, he noticed aspects of Philadelphia life that other artists missed — namely capturing realistic moments in the lives of black people in Philadelphia, making this one of the few paintings that focused on the experience of non-white men. Nathaniel Popkin, a historian and author of a historical fiction novel about Krimmel (Lion and Leopard, The Head and the Hand Press), notes that although the faces, body proportions, and stiff human stature show poor technique, the painting is notable because Krimmel was one of the few artists who avoided portraying African-Americans as caricatures or background scenery. This realistic painting demonstrates the critical role black carpenters and workers played in the building of America. “It reminds us of who did the laboring that built our cities,” Popkin says.

3. Fictional Techniques

Mount Holyoke College’s Staiti calls this painting “a blend of fact and fiction.” Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze depicts Washington and his men after the attack on Trenton in 1776, a crucial battle that boosted morale and ensured colonial control of New Jersey. Seventy-five years after the battle, Leutze presented the first President of the United States as a leader of exceptional courage and character, drawing upon stories gaining cultural traction about Washington cutting down a cherry tree and his refusal to lie about doing so. This mounting mythology laid the foundation for Leutze’s heroic — and historically inaccurate — interpretation of Washington. Despite the painting’s elder statesman vibe, Washington was much younger than he appears in the picture because Leutze used portraits from his older years as references. Also, as anyone with any boat experience knows, Washington wouldn’t have stood at the bow because he surely would have capsized the craft.

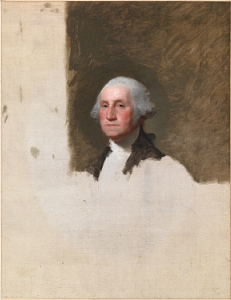

4. Dollar Signs

One of the most recognized images in the world, this unfinished portrait was used to make Washington’s engraving on the one-dollar bill. Stuart created several portraits of Washington, and this work was originally commissioned by Martha Washington with the goal of having a portrait of herself to accompany it. However, before its completion, the statesman died, and the portrait of Martha was never started. Its incomplete state proved beneficial: It made it easier to create copies later to sell, which he did. By the 1820s, the picture became the de facto image of Washington after Stuart created around 75 replicas that he sold and distributed to the public. The circulation power of the U.S. dollar serves as a critical engine driving its recognition. “It’s fair to say that it is the most reproduced image in all of human history,” Staiti says. “Nothing comes even remotely close.”

5. Revisionist History

During John Trumbull’s visit to Paris in 1817, Thomas Jefferson enlisted him to depict the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, a creation he hoped would ensure the recognition of his contributions. “Jefferson basically whispers in his ear, ‘Wouldn’t it be a great idea for you to paint a scene from 1776 in Philadelphia?’” Staiti says. Jefferson took an active role in this myth-making, since he believed his role in creating the Declaration of Independence was of the utmost importance. In fact, he had “Author of the Declaration of American Independence” carved on his tombstone above all his other accomplishments. However, Trumbull painted it so long after the event that Jefferson mangled some of the event’s details in his retelling. Thanks to Jefferson’s faulty and misguided memory, the blooper reel for the work of art includes the wrong furniture, inaccuracies in the seating arrangements, and an overemphasis on Jefferson’s role in the creation of the document. Despite those alternative facts, the painting enjoys a prominent placement: It sits in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, the home of Congress.

6. Pillar of Strength

This painting depicts the surrender of the British at the Battle of Yorktown, the decisive battle that led to the end of the Revolutionary War. It took years to make because John Trumbull traveled to the battle site and other countries to ensure the accuracy of the people and the place he sought to recreate. The painting’s messages of American strength and victory remain as potent as ever. For example, President Trump’s 2017 Holocaust Remembrance speech took place in the U.S. Capitol Building and featured the painting as a prominent backdrop. Staiti says the ceremonial value of being in the Capitol Building gives Trump the ability to connect American history with the present. “It was an attempt to connect Trump back to the values that buttress the beginning of the United States,” he says.

7. Honor Guard

Artist Charles Wilson Peale’s time as a lieutenant in the Pennsylvania militia and his participation in the battles of Princeton and Trenton gave him access to Washington that other artists failed to secure. Thanks to that access, he created this portrait as a commemoration of the twin victories, both turning points in the war. Peale completed the painting on orders from the State of Pennsylvania, and the portrait’s popularity sparked a demand for numerous replicas. Pennsylvanian officials thought the picture might prompt positive social change and inspire young people to emulate Washington by pursuing what was right for their nation. “They thought that was what a great nation does — you honor your leaders,” he says. Staiti says this desire to inspire younger generations also fueled the portrait’s popularity.

Cover photo is The Delaware Regiment at the Battle of Long Island by Domenick D’Andrea, 1776.