Twentieth-century politicians coined what we now call propaganda, but that doesn’t mean the American Revolution lacked messages created to encourage Americans to reconsider their relationship with the British Empire. “The patriot leaders had a big problem on their hands, which was how to turn their cultural cousins into enemies,” says Robert Parkinson, an assistant professor of history at Binghamton University. “The people who they looked up to for everything — how they talked, the books they read, for everything. How did they turn those people into enemies?”

To sway the colonists against their cultural cousins, patriots used cartoons, newspaper stories, paintings, and pamphlets, and despite the key characters’ reputation for truth-telling, much of the material was manipulative and effective. “Ben Franklin was one manipulative son of a bitch with the truth, making up all kinds of fake news stories and hoaxes to get the American populous to think what he thought,” says Parkinson. In later wars, message-crafters possessed a greater range of tools (radio, TV, and social media), and propaganda earned a bad reputation. But the goal of shifting citizens’ point of views remained constant. “When we think about propagandists, we think about really evil bastards like Joseph Goebbels,” says Parkinson. “We don’t want to think about John Adams and Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson as being in the same category as that guy. But I think they really were.”

Despite the unsavory similarities, it’s difficult to deny the common goals of evoking emotion by delivering messages to the colonists, says James Roger Sharp, a history professor at Syracuse University who specializes in American political history. “Propaganda was created as a means to persuade them into wanting their independence,” Sharp says. Here, the professors walk us through the three most powerful pieces of propaganda from the Revolutionary War:

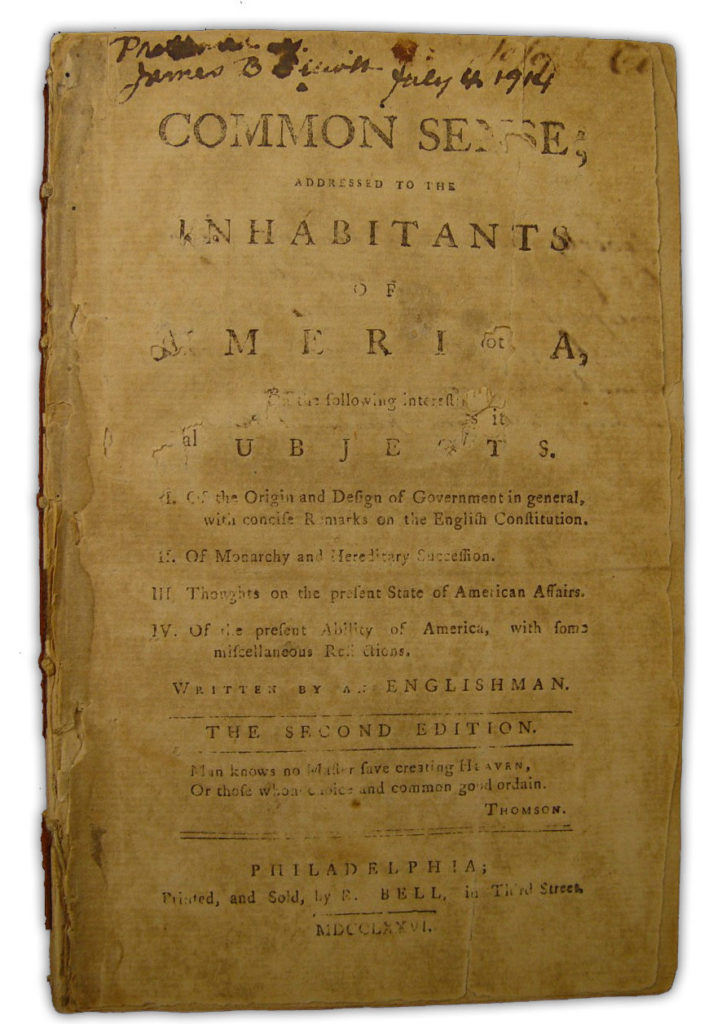

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

“One of the most important pieces of propaganda prior to independence was Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, which he published in January of 1776,” says Sharp. “Back in those days, propaganda was conveyed in many ways — cartoons and primarily through little pamphlets — this was an enormously popular pamphlet. Newspapers and pamphlets would be passed from person to person, but even without that, it was one of the most widely printed publications in the pre-revolutionary period.” The main purpose of the pamphlet was to ask the question, “Was it really common sense to stay in the British empire?” Sharp says. “Paine said, no that’s not common sense, why should we look to England to make these critical decisions when we are strong enough to be an independent country and should be making these decisions ourselves? So, this was a very important, probably the major piece of propaganda in the revolutionary period.”

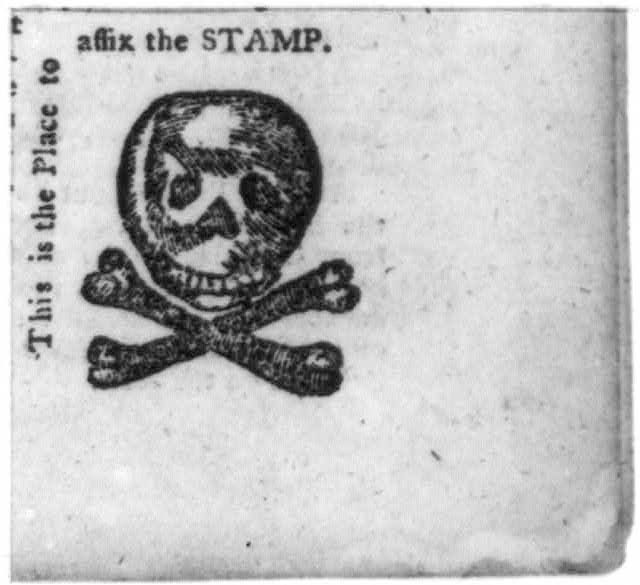

William Bradford’s Stamp Print

This print, which reads “This is the place to affix the stamp,” was designed and published by William Bradford, a printer during the Revolutionary War. The majority of the fervor that inspired propaganda like Bradford’s print was the result of one of America’s founders: Samuel Adams. “Samuel Adams had a way of turning events around and making political capital out of them,” says Sharp. “He produced a series of pamphlets that talked about the poor starving children in Boston because food couldn’t get in, basically making Britain the bad guy.” Sharp also points out that Adams possessed an ability to rally mobs. “After the Stamp Act and the Sugar Act, he did a great job of enlisting people to come out on the streets in Boston and show their displeasure,” Sharp notes, “and in some instances, rioting, burning down houses, tax collectors were tarred and feathered.”

The Murder of Jane McCrea, by John Vanderlyn

“I always point to this painting, which is [painted] long after the Revolution, by a New Yorker named John Vanderlyn, which is called The Murder of Jane McCrea,” says Parkinson. “He painted it in 1804. It’s actually a rendering of a semi-true story that happens right where Vanderlyn was born and raised in Glenview, New York, of this woman who is killed by Indians who are in John Burgoyne’s pay. It becomes this incredibly important story during the Revolution about this beautiful white woman who gets murdered by Indians, and the American leaders — like General Horatio Gates and members of Congress — are instrumental in making that story very, very popular. Every single newspaper in America publishes the news about Jane McCrea, and that’s because Patriot leaders made sure that those stories appeared, as it seemed to move people. It’s an iconic image.” While this image does not accurately represent all Native American involvement in the Revolution, its primary purpose was to inspire hatred against the Native American Loyalists, and, by extension, the British.

Cover photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.