Though history books often make no reference to their stories, women made critical contributions to the Revolutionary War. While men engaged in political maneuvering and populated the battlefields, women maintained homesteads, served as advisors and nurses, and some even stepped into battle. Time has erased the contributions of many of these women, but the stories of some remain memorable and bright. Re-enact asked five individuals involved in the preservation of 18th-century history to name their personal heroines of the American Revolution.

Angelica Schuyler Church, Political Power Broker

Sister-in-law to Alexander Hamilton and friend to many of America’s most famous political power brokers (Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Marquis de Lafayette), Church launched herself into political matters despite the prevalent belief that women should stay out of men’s affairs. “Her ability and willingness to wade right into politics is absolutely phenomenal,” says Ian Mumpton, a historical interpreter at the Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site. Mumpton says that while Hamilton was developing America’s financial system, Church sent him letters that outlined reading material about banks and finance that informed his efforts. Church is also credited for trying to arrange the rescue of Lafayette, who was arrested and placed in an Austrian prison during the French Revolution. Church used her influence and connections to make George Washington aware of Lafayette’s situation. A dive into Church’s letters demonstrates just how involved in societal affairs she really was.

Abigail Adams, Emotional Anchor

If the Revolutionary War era had a popularity contest, Abigail Adams would win in the favorite female category. She fought for women’s rights, and was an abolitionist and devoted therapist to her husband, John Adams. “She supported that cranky, old husband of hers for 54 years,” says Barbara Selletti, re-enactor at Germantown and academic librarian, researcher, history lecturer, and genealogist at Neumann University. “She ran his farm, raised their kids, but also served as an emotional anchor for him. Abigail was more than just a clever wife. She served as a sounding board and an advisor for Adams.” While her husband continuously traveled, Adams managed their home and farm and made investment decisions that would benefit the family. Uncommon at the time, Adams even wrote a will while her husband was alive, leaving most of her possessions to the women in her family instead of the men. But despite her husband’s crankiness, she loved him dearly. In fact, the letters between Adams and her husband demonstrate a compelling love story.

Phillis Wheatley, Word Warrior

Phillis Wheatley, the country’s first published African-American poet, was forced to the United States from West Africa as a child slave for the Wheatleys, a prominent family in Boston. Realizing her talent, the Wheatleys taught Phillis how to read and write. “She was a literary genius, a genius in bondage,” says Daisy Century, Ed.D., a first-person interpreter of Phillis Wheatley. “She was just so powerful with her words. She couldn’t go out and fight like the men in the war, so she fought with her pen.” By the time Wheatley was 18, she had written a collection of 28 poems. In 1773, with the help of Mrs. Wheatley, Phillis published the collection, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, which by then had expanded to include 39 poems. Throughout her short life (she died at 31 in 1784), Phillis continued to write poetry, using her work to comment on the themes of slavery and the ideals of rebellious colonists while America still fought for its independence.

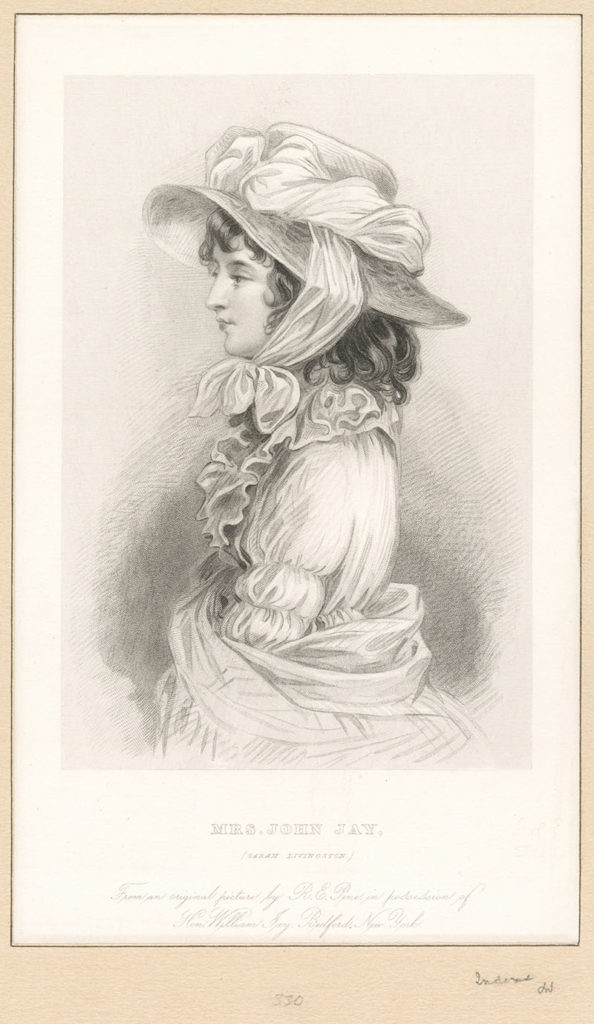

Sarah (Sally) Livingston Jay, America’s Hostess

Sally Jay was the wife of often forgotten Founding Father John Jay. Due to Jay’s political responsibilities as the president of the Continental Congress and subsequent minister to Spain, the two were often separated, which caused Sally considerable loneliness. To be closer to her husband, she left everything she knew — her family, and their young son Peter, to join him in Spain. When Jay was dispatched to France to broker the Treaty of Paris, Sally followed. “If she wasn’t there, I don’t think we would have had the Treaty of Paris,” Phil Webster, first-person interpreter of John Jay, says. Webster says the presence of Sally and their infant daughter Maria (born while the Jays were in Spain) helped to alleviate the tension in the room. In later letters, Benjamin Franklin often inquired about how Maria was doing. In France, Sally would often attend and hold social events, helping to build a bridge between America and France. When the Jays returned to New York, Sally continued her social event planning, throwing dinner parties for diplomats and notables that served as opportunities for Constitutional lobbying.

Mary Perth, Slave Survivor

A slave in Norfolk, Virginia, Mary Perth proved a resilient and heroic woman (but no images of her exist). Thanks to a gift of the New Testament given to her by her owner, she learned to read and then possibly shared that ability with other slaves by reading scripture to them. As rebellious colonists were about to enter into the War for Independence, Perth’s slaveowners remained loyal to the British and so did she, becoming a Black Loyalist, says Hope Wright, actor-interpreter at Colonial Williamsburg. That allegiance created challenges for Perth and the Willoughby’s, her owners, who fled American patriots and sought refuge with the British at an encampment that endured a deadly smallpox outbreak. Mary and her daughter, Patience, survived and fled with other loyalists to New York. There, she was separated from the Willoughby family, worked as a domestic, and met and married Caesar Perth. The couple acquired certificates of freedom and fled to Nova Scotia, where they faced a hostile reception, a harsh climate, and discrimination. The couple relocated again to Freetown, Sierra Leone based on promises of land, education, self-governance, and equality. But the Perths and other black settlers struggled to earn these things. Caesar died not long after he finally built a home on the land they had been promised. Mary sold the farm, turned her home into a boarding house, and survived an attack on Freetown by the French. She left West Africa as a housekeeper for the governor, who moved to London, and ultimately returned to Nova Scotia, where she died.

Cover photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.